What Is Chinese New Year About?

Red lanterns strung between apartment blocks. The echo of firecrackers bouncing off tower walls. Families gathered around banquet tables, passing dumplings and stories from one generation to the next. This is Lunar New Year in China — part legend, part ritual, and all heart.

For travelers, it’s one of the most captivating times to be in the country. For locals, it’s a season of homecomings, family ties, and timeless traditions. Here’s everything you need to know about the holiday also known as Spring Festival — from its mythological roots to modern celebrations.

Where it all began

Lunar New Year dates back more than 3,000 years to the Shang Dynasty, where seasonal rituals marked the start of the agricultural calendar. But the traditions we know today — red decorations, firecrackers, lion dances — stem from an old folk tale about a terrifying beast named Nian (年獸).

Legend has it that Nian emerged once a year to terrorize villages. It feared only three things: noise, fire, and the color red. Villagers began lighting firecrackers, wearing red clothes, and hanging crimson scrolls to scare it away — and it worked. Over time, this victory turned into a national celebration.

Celebrating the season

Unlike the fixed Gregorian calendar, Lunar New Year shifts each year based on the moon. The holiday kicks off with the first new moon of the year and lasts 15 days, culminating in the Lantern Festival.

Key traditions include:

Cleaning the house to sweep away bad luck.

Reunion dinners on New Year’s Eve with symbolic dishes like dumplings (for wealth) and fish (for abundance).

Red packets (紅包 hóngbāo) filled with cash, gifted to children and unmarried adults for good fortune.

Decorating homes with red couplets, paper cuttings, and lucky symbols.

In some households, you’ll still find a picture of the Kitchen God, his lips dabbed in honey so he only whispers sweet reports to the Jade Emperor.

The world’s biggest migration

Every year, over 1 billion journeys are made in China in the lead-up to Lunar New Year. This mass migration — known as Chunyun (春運) — sees migrant workers, students, and city dwellers returning to their hometowns to celebrate with family. It’s the largest annual movement of people on Earth.

Train stations buzz with energy. Long-haul buses fill to capacity. And across the country, there's one shared goal: to be home for the holidays.

Food with meaning

Like most festivals in China, Spring Festival is anchored by food. But these aren’t just delicious dishes — they’re symbols of hope and prosperity:

Dumplings (餃子 jiaozi): Resemble ancient silver ingots. Eating them = welcoming wealth.

Fish (魚 yú): Sounds like "surplus." Families often save part of the fish to "carry over" into the new year.

Nian gao (年糕): A sticky rice cake whose name sounds like “year high,” implying growth.

Tangerines and oranges: Symbols of luck and wealth, often displayed or gifted.

Each region has its own festive dishes, from sweet rice balls in the south to stir-fried leeks in the north — but the intention is always the same: to eat well and wish well.

The animals of the zodiac

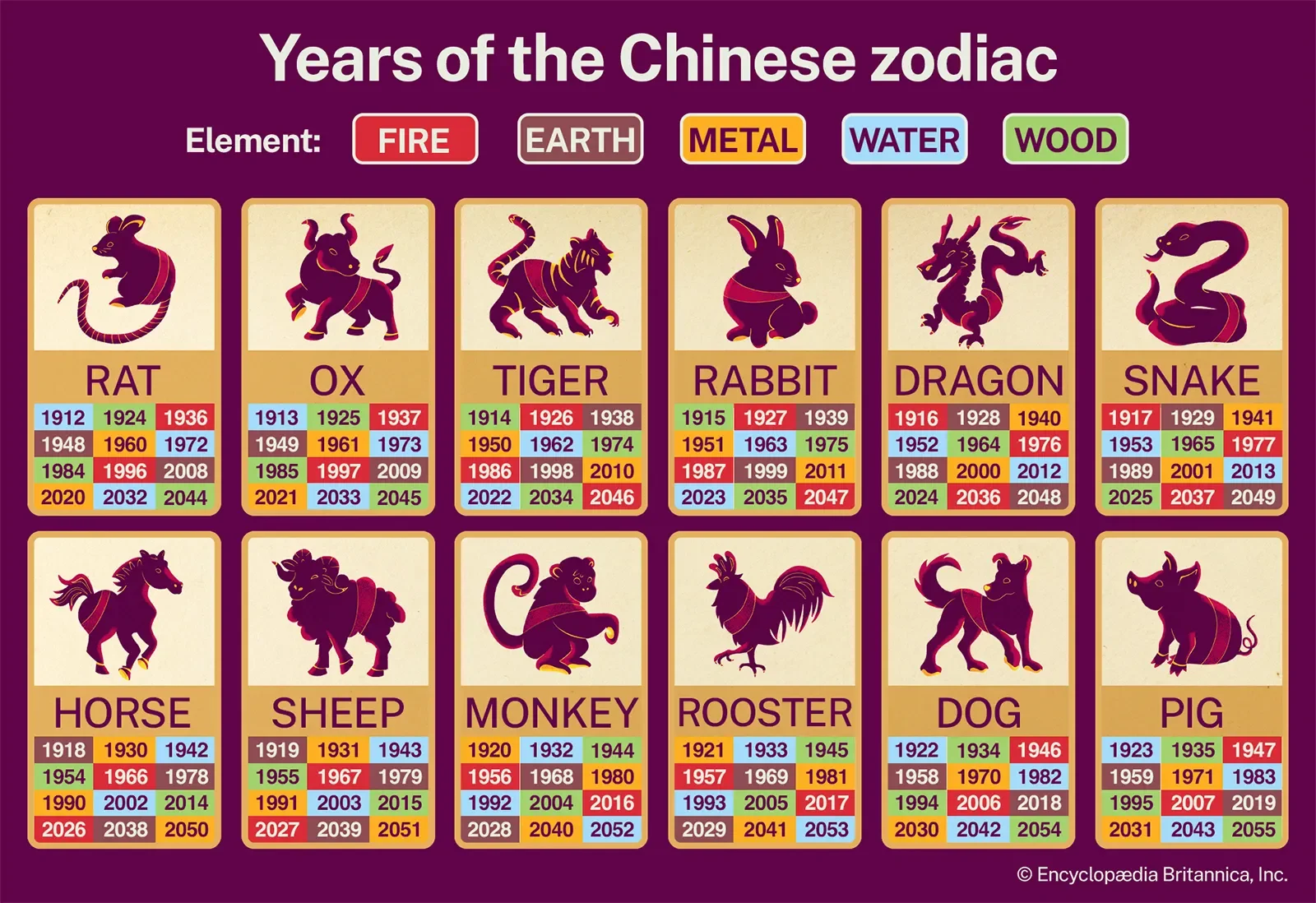

The Chinese zodiac follows a 12-year cycle, each year associated with an animal. The order: Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, and Pig.

Each animal carries its own set of characteristics, and your birth year is believed to shape your personality and destiny. For example, those born in a Dragon year are said to be ambitious and charismatic, while Rabbits are seen as kind and intuitive.

A global celebration

While known globally as Chinese New Year, this holiday is celebrated across East and Southeast Asia — with unique names and customs:

Vietnam: Tết, the biggest holiday of the year, includes peach blossoms and lucky money.

Korea: Seollal, celebrated with tteokguk (rice cake soup) and ancestral rites.

Mongolia: Tsagaan Sar, a time for family reunions and dairy feasts.

Even outside of Asia, cities like London, San Francisco, and Sydney host grand parades and public festivities, connecting diaspora communities and travelers alike.

From ancient legends to modern firework bans, Lunar New Year remains a celebration of continuity, family, and fresh starts. Whether you’re slurping noodles in a Beijing hutong or catching lion dances in a Chinatown abroad, the spirit of the season is universal: out with the old, in with the luck.